Is the 15 minute city having its 15 minutes of fame, or is it here to stay?

Holly Harrington discusses what the 15 minute city could mean for our capital

The current pandemic has given us all pause for thought and seeing our once vibrant, buzzing cities empty and desolate suggests it is also time to think about the future city. Recently revived by Anne Hidalgo, Mayor of Paris, and Carlos Moreno, the world and his dog are looking at the 15 minute city concept, what it is, what it looks like and how we can do it.

The idea of a 15 minute city is not an entirely new one, but one which has been discussed for decades back to Jane Jacobs, and William H Whyte. Jacobs touted that proximity is the key in The Life and Death of Great American Cities. Here we are many years later with real cause to investigate these theories again.

The idea is that most things we need on a daily basis can be found within a specific walking or cycling radius from our homes. This automatically brings to mind a town rather than a city. So what would this mean for our capital and global cities like London? How does this idea of a much more local town-like environment fit into a large, complex, sprawling city?

During my diploma studies, I started exploring boundaries, borders and identities of areas, mainly in the Lea Valley area. My research led me to realise that London has done well to hold on to distinct characteristics and cultures of each borough despite being part of a larger agglomeration. To me it seemed as if all these separate boroughs and areas within were like islands of their own distinct character. Urban islands, if you will, with borders and boundaries of their own but still connected to the adjacent areas which still played a part in the overall archipelago that is London. Roads, cycle lanes, distribution networks, green spaces and wetlands present themselves as the sea flowing between each of these islands - replenishing each area and supplying other islands with their needs.

This flowing tide of people, circulation and supply has been altered more towards one direction lately - like our environmental situation - to that of a less sustainable one. The pull of the city centre has become the mother island pulling all resources inwards and draining the other islands of their people and facilities. Of course this is to a certain degree the natural order of a city versus a town and my personal opinion is that this will not radically change as otherwise we would no longer have cities but many, many towns. This is not a solution that anyone wants, yet a rearrangement or shift in this balance could benefit us all - which is what the ‘ville du quart d’heure’ suggests.

The first thing to look at would be our planning system. The current system designates land for particular uses where residential is generally kept separate to commercial, retail, and industrial uses. In some cases this resulted in areas like Canary Wharf which is mainly an island of offices and used to be plagued by solitude at weekends. On the other hand we also have primarily residential areas with very few facilities nearby unless you hop on a tube to central. The 15 minute city approach turns this on its head and promotes a more diverse set of land use within a smaller area, meaning residential, commercial, civic, educational and even light industrial could be in much closer proximity to one another. This zoning system has formed our cities, as our actual 9-5 has. New transport systems extend further out into the countryside carrying us to work in the city centre. Caffination stations, and other retail, line our routes from the train stations to the main working areas to help revive us from potentially long and stressful journeys; where some of us have to fight for space on crowded buses, tubes or trains. With so many workplaces and facilities located mainly in the city centre, it has pulled people away from our local areas for the majority of the week causing our high streets to dwindle and die.

Our daily commutes have become the main arterial routes, and while ever expanding to accommodate growing demand it also appears eternally insatiable to the daily need of commuters. The recent pandemic however, has halted the daily rat race, giving us an opportunity to review, adapt and create a ‘new normal’. Our daily rhythm has already shifted and most of us do not miss the commute. We are now offered a rare opportunity to review how we inhabit, navigate and form our cities going forwards, with the hope of readjusting these tides and the potential erosion of smaller islands.

So how could we do this in London?

Thanks to London’s pre-industrial roots, local assets such as high streets and local hubs are already there and waiting for us to embrace them again. According to studies by the Greater London Authority, 90% of the population has access to a high street within 10 minutes of their home.

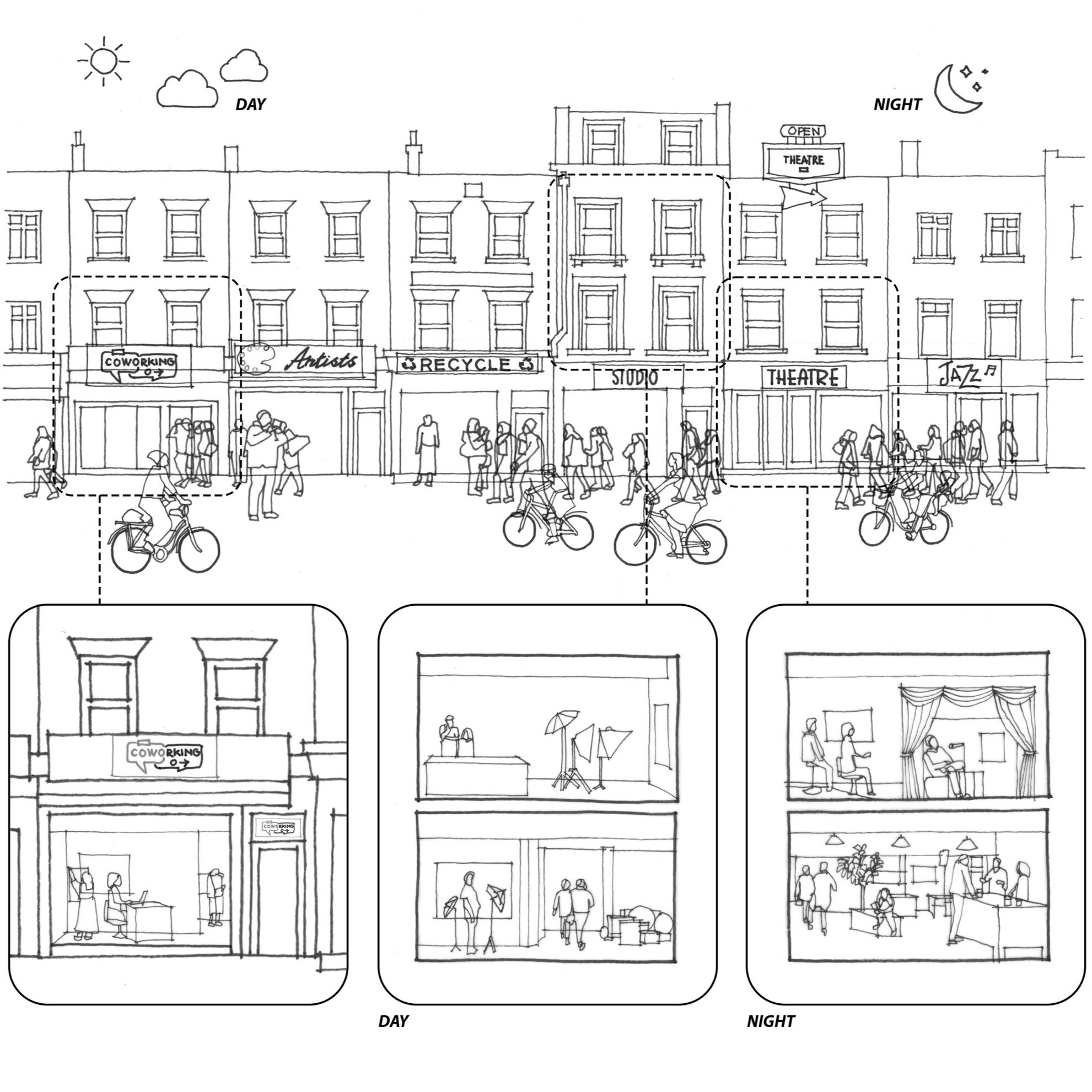

During the many lockdowns, most of us started relying on our local high street again for basic needs, the ever important daily life-saving coffee, as well as brief physical outlets like a ten minute walk outside the house. Using these high streets could enable a 15 minute city with a network of reinvigorated islands. There is a clear opportunity to insert any missing facilities, like flexible co-working spaces, cafes, and cycle shops, into vacant and under-used spaces and retail units. Shop fronts could also be reactivated for different uses like live/work studio units which could double up as retail and gallery spaces for artists and makers. Bringing people back to the area for certain portions of the week by enabling flexible working, will mean people will buy lunch, groceries, and other daily needs on the high street again thus boosting the local economy. These starter high streets could then act as catalysts for the growth of these smaller hubs within the overall mother city. With a series of more intensified and activated local hubs, it will not only be the city centre that could be vibrant throughout the day and night. Scale is important however, as we cannot create new universities, hospitals and stadiums every 30 minutes across London. In this sense a 15 minute ‘city’ may be slightly misleading. What we want is a network of smaller activated hubs that work together like an archipelago.

Whilst this would mean the decentralisation of the city centre to a certain degree, this does not mean the death of the city centre. Far from it, I believe. The concept is not to relieve the city centre from its purpose entirely, nor to decant all uses and facilities to surrounding areas, but rather to ease the load and create more balance. We would need to flip our current planning strategy of zoning, allowing the city and our surrounding areas to become much more dynamic, vibrant islands than before. If we insert certain additional facilities into primarily residential areas, we then may need to insert different facilities into the city centre. Ideally we re-use and adapt any vacant office space to provide multi-facilities to enable CBDs to become 15 minute cities of their own. Just like the smaller islands, the city centre will also reinvigorate itself, bringing both activities and people back; such as food markets, housing and creative industries that may have been pushed out over the past decades thus making the city even more exciting than before.

Whilst some of the ideas seem like they are big changes, I think a perspective shift is required from all of us who inform, create and manage cities in their built and social form to allow this slight shift towards a more sustainable lifestyle. In truth I believe these changes could boost local economies, potentially creating more jobs, which could in turn boost the economy overall. We are merely in times of change, which means our view of the city, what it is, how it looks and how we inhabit it should also change.

My view of the 15 minute city is ultimately about flexibility and choice for everyone who inhabits it. We would have the option to work from home, work locally, and still work in the city centre for part of the week or every day still if we choose.

If any silver linings are to be found out of this crisis it is that we are adaptable and resilient. Our cities should follow this lead. In my earlier research I was proposing London as Archipelago-polis or a connected set or urban islands that work together to make a whole. The idea was that by embracing, enhancing and activating these unique islands and their connections to other islands, local culture could be retained and we could avoid the sprawl of glass skyscrapers and global architecture that doesn’t respond to its surroundings. Six years on from that research, it seems that a series of urban islands links in very well with the 15 minute city concept and could very well become a new manifesto for London.

Copenhagen, Sweden, Amsterdam and several cities in China have all embraced this concept in the recent years and have already started upon several legislative and supporting infrastructure developments. Considering these moves were made before the pandemic, there is evidently validity in many of its principles. Barcelona is not Paris, and neither is London so each city across the world will have to review what this means to them, their culture and how best to implement the approach. With a new outlook on our daily and working lives, I am sure many of us would like the ease and flexibility that less commuting and more proximity could provide. Whilst the idea is having its 15 minutes of fame, I think it is safe to say it may not only be wishful thinking and could be the beginnings of our future cities.

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay up to date with all of our news and stories.